Bearings

Sharing is a Gift in Itself

Congregations becoming Spaces of Hospitality for People Experiencing Homelessness

By Courtney Tabor

October 2019 Issue

Yesterday I spent several hours at church, but not for the reasons you might think. This was not for a worship service or a committee meeting. It was neither quiet nor serious. The evening I spent at church was filled with noise and children and purple frosting. It was filled with running toddlers, balloons, and at least four different spoken languages. When I got home, I had a full belly and an overflowing heart. I was at church yesterday to spend the evening with families experiencing homelessness.

I am the Program Director for Greater Portland Family Promise (GPFP), an organization based in Maine. Greater Portland Family Promise is an affiliate of the national Family Promise program, which has 210 affiliates across the country. Family Promise serves children and their families who are experiencing homelessness by providing shelter, food, case management, and community support while helping them to establish sustainable living situations. GPFP provides these services through a network of hundreds of trained volunteers and through partnerships with local faith communities. GPFP is not a faith-based organization, but utilizes the resources that exist within faith communities in order to support families in need.

In the Family Promise model, an interfaith network of congregations takes turns sheltering families in a weekly rotation. When it is their turn to host, volunteers from the congregation turn the facility into a home. Volunteers transform sanctuaries and fellowship halls into dining rooms, living rooms, and playrooms. They make meeting rooms and Sunday school classrooms into bedrooms by setting up beds, lamps, and plenty of cozy blankets. Kids make colorful welcome signs for each family and put them on the bedroom doors. For that week, from Sunday evening until the following Sunday morning, that congregation becomes a home.

In this model, hospitality is key. Families being served are referred to as "guests," and volunteers are their "hosts." When families arrive at the congregation on Sunday evening, volunteers have prepared a meal for them. Guests and hosts eat together at a common table. They share in conversation and spend the evening together. Volunteers play with the children, help with homework, and talk with parents. At night, each person has a comfortable bed to sleep in and every family has a private room of their own. Hosts are there in the morning to make tea and coffee, set out breakfast, and see the families off as they leave for daytime activities. Family Promise staff work with families during the daytime to secure housing and other key resources.

The events precipitating homelessness vary, but here in Portland, Maine, the overwhelming majority of families in the program are experiencing homelessness because they are newly arrived in the United States and seeking asylum. Some 87% of the families in our program are asylum seekers, having fled their home countries in African nations such as Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo. In addition to the challenges of homelessness, these asylum-seeking families have been through unimaginable trauma in their home countries. In recent months, many families have come through the southern border of the U.S., after traveling through up to thirteen countries on foot or by boat in treacherous conditions. The journey can take many months, often ending in detention at the border. When families without homes arrive in Portland, their exhaustion is palpable and their pain even more so. They have been told over and over again that they are not welcome. At Greater Portland Family Promise, we do everything we can to change that narrative, to let our families know that we are so glad they are here.

Although I work for Family Promise, last night I spent the evening with families as a host. This gave me the opportunity to interact with families in a different capacity and in a more relaxed environment.

Before my hosting shift began, my co-volunteer informed me that it was her wedding anniversary. Her husband planned to volunteer as well, and they were going to bring a cake to share with everyone as a celebration. I offered to find someone to cover for her so that she and her husband could celebrate together without having to volunteer. “No,” she insisted. “We want to do this.”

As a mini-surprise, I brought a few art supplies to the church in hopes that the guest children might make an anniversary card or two. I explained my plan to Beatrice (not her real name), one of the mothers in our program. Beatrice is Congolese and speaks Lingala. I, unfortunately, do not speak a word of Lingala, but we both have enough French to get by. So we whispered in somewhat broken French, and made a plan.

Beatrice gathered up the children and put them to work drawing pictures. I expected a 10-minute project, but 45 minutes later, the families were still working and did not want to stop for dinner. While the kids drew pictures, the rest of the adults joined in as well, building rainbow-colored paper chains and hanging them all over the room. “It’s a party, isn’t it?” they asked. “We love a party!”

We shared a meal together, sang together, had cake and ice cream together. A three-year-old, hyper from the sugary dessert, ran gleefully around the room and convinced us to let her put purple frosting on our noses.

For me, this evening spent with families painted a perfect picture of the beauty of the human spirit. What a gift it is when two people choose to spend their anniversary not at a fancy restaurant, but instead at a church, bringing cake and ice cream, and even the roses along with them, sharing a table with families experiencing homelessness and volunteer hosts. What a gift it is when families who have been through trauma upon trauma, who have suffered violence and displacement and terror, still have the capacity for laughter, for singing, for filling a room with colorful paper chains. These families, who have had so much taken away from them, still have the capacity to give with such abundance and uninhibited joy.

Working with families experiencing homelessness helps me daily to see the resiliency of the human heart. Joy and laughter does not mean life isn’t hard. The families we work with are exhausted, they are frustrated, they are scared; but with loving hospitality we can show our neighbors that they are not forgotten.

Hospitality is a way to respect the dignity of our neighbors. We have a responsibility to one another to respect the humanity that lies within all of us. This is where we consistently tend to fall short. When we cannot see people as human, we cannot care about their dignity.

Homelessness is a trauma that threatens to strip people of their dignity. This is in part because of a lack of access to basic human needs. It is also in part because we as a society treat homelessness as a failure of those experiencing it. Most of us who have homes and a sense of stability cannot or do not want to imagine ourselves as homeless. In our homes, we feel invincible. The problem with this invincibility narrative is that, since we assume it could never be us, we look at those who experience homelessness with blame. It is a short distance from separation to blame, and from blame to dehumanization. Dignity no longer seems important. Marginalization makes no space for dignity. Marginalization only makes space for pity, disdain, humiliation, shame, and fear.

Hospitality has the power to change that. Radical, intentional hospitality has the power to change hearts and communities.

When someone experiencing homelessness encounters authentic hospitality, they are reminded that they are valued, that they matter, that they are loved. When someone has no place to call their own, there is great power in being told, “We have prepared a space for you. We are so very glad that you’re here.” However, hospitality does not stop there. At Family Promise, we ask volunteers to treat families as if they were guests in their homes. Mealtime is a perfect example. Hosts and guests eat a meal together at the same table, they eat the same food, they talk together, they learn each other’s names, they even clean up and wash the dishes together. Relationships are built over plates of spaghetti, bowls of ice cream, and sinks full of soap suds.

For the host, these relationships blur and break down lines of separation between “us” and “them” that have been so deeply ingrained in our minds. A volunteer’s image of homelessness begins to change. They no longer imagine homelessness to mean a faceless beggar on the street. Instead they remember the face of the mother they sat with at dinner or the child to whom they read a story. When volunteers practice radical hospitality and begin to form relationships, their hearts become engaged and they are inspired to keep coming back. They are inspired to share their cake and roses and joy on the night of their wedding anniversary because sharing is in itself a gift.

For the guests, encountering this radical hospitality can be equally transformative. Sharing in fellowship over spaghetti or ice cream or soap suds says to the guest, “Maybe I am worthy. Life is really hard right now, but here is this person smiling at me across the table, calling me by my name. This person thinks I matter.” When guests can continue to make these connections, their worth is validated. There is space for them to feel a bit of joy in the midst of the challenges they are facing. When guests experience some of the hardest times of their lives, and yet are welcomed with warmth and care, they can give their worry just a little break while they immerse themselves in making paper chains for a party. Kindness helps nurture resilience.

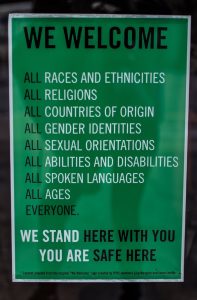

In the current political and religious climate, people experiencing homelessness, immigrants, and so many others are being forced further and further to the margins of society. Our country’s policies create harsh conditions for our poorest residents, and the rhetoric used by our political leaders—and often even our next door neighbors—supports closing doors rather than opening hearts. In the face of this extreme unwelcome, our practices of hospitality must be equally radical. Our responsibility as people of faith and of social consciousness is to say to our new neighbors, “Yes, you matter. Yes, you are worthy. Yes, this is a space for you.”

In the current political and religious climate, people experiencing homelessness, immigrants, and so many others are being forced further and further to the margins of society. Our country’s policies create harsh conditions for our poorest residents, and the rhetoric used by our political leaders—and often even our next door neighbors—supports closing doors rather than opening hearts. In the face of this extreme unwelcome, our practices of hospitality must be equally radical. Our responsibility as people of faith and of social consciousness is to say to our new neighbors, “Yes, you matter. Yes, you are worthy. Yes, this is a space for you.”

Whether it is through a model like Family Promise or another model entirely, church communities have the opportunity to consider how they can become spaces of hospitality for those who have no safe space to call their own. What makes a difference is making people feel welcomed—not as objects of pity but rather as key players in mutually authentic relationships.

At a time when too many people practice discrimination and hatred in the name of faith, Christians of conscience have the absolute responsibility to be agents of love without barriers. For people experiencing homelessness, the barriers are so, so many, but practices of hospitality, kindness, and authentic human love can help tremendously.

Of course, homelessness is messy. It is traumatic and exhausting and terrifying. When we sit at the table with someone experiencing homelessness, when we can say, “I’m so glad you’re here,” that is what can free people to fill a room with color. We have to be ready, then, to get our hands dirty, and, from time to time, to get our noses covered with frosting.

Photo Credits:

Spencer Davis, "Sharing a Meal" (August 2, 2019). Via Unsplash. CC2.0 license.

Image #1. Niklas Nosber, "Cupcakes, Lichtspiele, Reflektion - Ich mag diese Folie" (August 18, 2019). Via Unsplash. CC 2.0 license.

Image #3. Brittani Burns, "I love Asheville" (August 11, 2018). Via Unsplash. CC 2.0 license. Cropped.